As he later wrote, “ur purpose, as it evolved in the late 1960s, was to apply the critical standards of to the ideology and sensibility of, and occasionally vice-versa.” In fiction that meant that such essentially countercultural sensibilities as Brautigan, Robbins, Stone, and Apple cohabited with Postmodernists Coover, Barth, Elkins, and Gass and more traditional writers like Moore, Powers, and Pritchett.

In many senses a classic New York intellectual, with all that implies, Solotaroff paired his highbrow tendencies with the conviction that, as he put it, “Literature was too important a democratic resource to be left to the literati.” The country was in more or less permanent crisis during NAR’s years of publication, and it engaged with the period’s vertiginous sense of cultural free fall in a fashion that exquisitely calibrated openness to the new with old-school rigor. Solotaroff kept this dubious economic proposition afloat for 11 years on sheer excellence, and none of the back-office strain that eventually did in NAR showed in its consistently glittering contents.

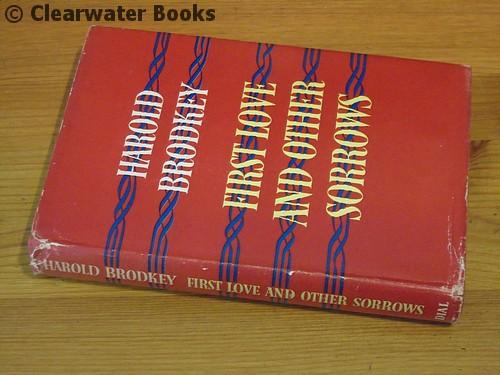

Its gilt-edged roster of poets featured Allen Ginsberg, John Ashbery, John Berryman, Richard Hugo, James Welch, Sylvia Plath, A.R. Its brainy and ultraengaged essays included Gass’ “Fiction and the Figures of Life,” Ellen Willis’ “Lessons of Chicago,” Leslie Epstein’s “Walking Wounded, Living Dead” (an astonishing meditation on the return of the Living Theatre from exile, and perhaps the most penetrating thing ever written about the ‘60s crackup), Norman Mailer’s “A Course in Film-Making” (a chest-beating account of the making of Maidstone), and superb work from Stanley Kauffmann, Richard Gilman, George Dennison, Peter Handke, Wilfrid Sheed, Albert Goldman, Paul Zweig, and Theodore Roszak. Alvarez’s The Savage God, and Marshall Berman’s lyric apologia for radical striving, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. Nonfiction works that debuted in NAR included Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, Michael Herr’s Dispatches, A. Doctorow’s Ragtime and Robert Coover’s The Public Burning first appeared in its pages. It published Harold Brodkey’s notorious cunnilingual epic “Innocence,” with its immortal line “To see her in sunlight was to see Marxism die.” E.L. Powers, and William Gass ("In the Heart of the Heart of the Country”). Powers, Cynthia Ozick, Stanley Elkin, Donald Barthelme ("Robert Kennedy Saved From Drowning”), Russell Banks, Ralph Ellison, J.F. Pritchett, Grace Paley (“Faith: In a Tree”), Robert Stone, Ian McEwan (three of his earliest stories), Jorge Luis Borges, Gilbert Sorrentino ("The Moon in Its Flight”), Brian Moore, J.F. Its roster of fiction included work by Philip Roth (two pieces from Portnoy’s Complaint and “I Always Wanted You To Admire My Fasting: Looking at Kafka”), Leonard Michaels, Gabriel García Márquez, Max Apple (“The Oranging of America”), John Barth, Tom Robbins, Susan Sontag, V.S.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)